John Brown (abolitionist)

John Brown | |

|---|---|

Brown in a photograph by Augustus Washington, c. 1846–1847 | |

| Born | May 9, 1800 Torrington, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | December 2, 1859 (aged 59) Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia), U.S. |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Resting place | North Elba, New York, U.S. 44°15′08″N 73°58′18″W / 44.252240°N 73.971799°W |

| Monuments | Various:

|

| Known for | Involvement in Bleeding Kansas; Raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. |

| Movement | Abolitionism |

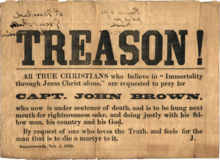

| Criminal charge(s) | Treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia; murder; inciting slave insurrection |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 20, including John Jr., Owen, and Watson |

| Parent | Owen Brown (father) |

| Signature | |

John Brown (May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859) was an American abolitionist in the decades preceding the Civil War. First reaching national prominence in the 1850s for his radical abolitionism and fighting in Bleeding Kansas, Brown was captured, tried, and executed by the Commonwealth of Virginia for a raid and incitement of a slave rebellion at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859.

An evangelical Christian of strong religious convictions, Brown was profoundly influenced by the Puritan faith of his upbringing.[1][2] He believed that he was "an instrument of God,"[3] raised to strike the "death blow" to slavery in the United States, a "sacred obligation."[4] Brown was the leading exponent of violence in the American abolitionist movement,[5] believing it was necessary to end slavery after decades of peaceful efforts had failed.[6][7] Brown said that in working to free the enslaved, he was following Christian ethics, including the Golden Rule,[8] and the Declaration of Independence, which states that "all men are created equal."[9] He stated that in his view, these two principles "meant the same thing."[10]

Brown first gained national attention when he led anti-slavery volunteers and his sons during the Bleeding Kansas crisis of the late 1850s, a state-level civil war over whether Kansas would enter the Union as a slave state or a free state. He was dissatisfied with abolitionist pacifism, saying of pacifists, "These men are all talk. What we need is action – action!" In May 1856, Brown and his sons killed five supporters of slavery in the Pottawatomie massacre, a response to the sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces. Brown then commanded anti-slavery forces at the Battle of Black Jack and the Battle of Osawatomie.

In October 1859, Brown led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (which later became part of West Virginia), intending to start a slave liberation movement that would spread south; he had prepared a Provisional Constitution for the revised, slavery-free United States that he hoped to bring about. He seized the armory, but seven people were killed and ten or more were injured. Brown intended to arm slaves with weapons from the armory, but only a few slaves joined his revolt. Those of Brown's men who had not fled were killed or captured by local militia and U.S. Marines, the latter led by Robert E. Lee. Brown was tried for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, the murder of five men, and inciting a slave insurrection. He was found guilty of all charges and was hanged on December 2, 1859, the first person executed for treason in the history of the United States.[11][12]

The Harpers Ferry raid and Brown's trial, both covered extensively in national newspapers, escalated tensions that in the next year led to the South's long-threatened secession from the United States and the American Civil War. Southerners feared that others would soon follow in Brown's footsteps, encouraging and arming slave rebellions. He was a hero and icon in the North. Union soldiers marched to the new song "John Brown's Body" that portrayed him as a heroic martyr. Brown has been variously described as a heroic martyr and visionary, and as a madman and terrorist.[13][14][15]

Early life and family

Family and childhood

John Brown was born May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut,[19] the son of Owen Brown (1771–1856)[a] and Ruth Mills (1772–1808).[22] Owen Brown's father was Capt. John Brown, of English descent, who died in the Revolutionary War in New York on September 3, 1776.[23] His mother, of Dutch and Welsh descent,[24] was the daughter of Gideon Mills, an officer in the Revolutionary Army.[23]

Although Brown described his parents as "poor but respectable" at some point,[22] Owen Brown became a leading and wealthy citizen of Hudson, Ohio.[23][25] He operated a tannery and employed Jesse Grant, father of President Ulysses S. Grant. Jesse lived with the Brown family for some years.[25] The founder of Hudson, David Hudson, with whom John's father had frequent contact, was an abolitionist and an advocate of "forcible resistance by the slaves."[26]

The fourth child of Owen and Ruth,[22][b] Brown's other siblings included Anna Ruth (born in 1798), Salmon (born 1802), and Oliver Owen (born in 1804).[27][28] Frederick, identified by Owen as his sixth son, was born in 1807.[29] Frederick visited Brown when he was in jail, awaiting execution.[30] He had an adopted brother, Levi Blakeslee (born some time before 1805).[31] Salmon became a lawyer, politician, and newspaper editor.[29]

While Brown was very young, his father moved the family briefly to his hometown, West Simsbury, Connecticut.[23] In 1805, the family moved, again, to Hudson, Ohio, in the Western Reserve, which at the time was mostly wilderness;[32] it became the most anti-slavery region of the country.[33] Owen hated slavery[34] and participated in Hudson's anti-slavery activity and debate, offering a safe house to Underground Railroad fugitives.[35] Owen became a supporter of Oberlin College after Western Reserve College would not allow a Black man to enroll.[36] Owen was an Oberlin trustee from 1835 to 1844.[36] Other Brown family members were abolitionists, but John and his eccentric brother Oliver were the most active and forceful.[37]

John's mother Ruth died a few hours after the death of a newborn girl in December 1808.[38] In his memoir, Brown wrote that he mourned his mother for years.[39][40] While he respected his father's new wife,[39][40] Sallie Root,[29] he never felt an emotional bond with her.[39][40] Owen married a third time to Lucy Hinsdale, a formerly married woman.[29] Owen had a total of 6 daughters and 10 sons.[29]

With no school beyond the elementary level in Hudson at that time, Brown studied at the school of the abolitionist Elizur Wright, father of the famous Elizur Wright, in nearby Tallmadge.[41] In a story he told to his family, when he was 12 years old and away from home moving cattle, Brown worked for a man with a colored boy, who was beaten before him with an iron shovel. He asked the man why he was treated thus, and the answer was that he was a slave. According to Brown's son-in-law Henry Thompson, it was that moment when John Brown decided to dedicate his life to improving African Americans' condition.[42][43] As a child in Hudson, John got to know local Native Americans and learned some of their language.[22] He accompanied them on hunting excursions and invited them to eat in his home.[44][45]

Young adulthood

At 16, Brown left his family for New England to acquire a liberal education and become a Gospel minister.[46] He consulted and conferred with Jeremiah Hallock, then clergyman at Canton, Connecticut, whose wife was a relative of Brown's, and as advised proceeded to Plainfield, Massachusetts, where, under the instruction of Moses Hallock, he prepared for college. He would have continued at Amherst College,[41][47] but he suffered from inflammation of the eyes which ultimately became chronic and precluded further studies. He returned to Ohio.[23]

Back in Hudson, Brown taught himself surveying from a book.[48][c] He worked briefly at his father's tannery before opening a successful tannery outside of town with his adopted brother Levi Blakeslee.[41] The two kept bachelor's quarters, and Brown was a good cook.[41] He had his bread baked by a widow, Mrs. Amos Lusk. As the tanning business had grown to include journeymen and apprentices, Brown persuaded her to take charge of his housekeeping. She and her daughter Dianthe moved into his log cabin. Brown married Dianthe in 1820.[49] There is no known picture of her,[50] but he described Dianthe as "a remarkably plain, but neat, industrious and economical girl, of excellent character, earnest piety, and practical common sense".[51] Their first child, John Jr., was born 13 months later. During 12 years of married life Dianthe gave birth to seven children, among them Owen, and died from complications of childbirth in 1832.[52]

Brown knew the Bible thoroughly and could catch even small errors in Bible recitation. He never used tobacco nor drank tea, coffee, or alcohol. After the Bible, his favorite books were the series of Plutarch's Parallel Lives. He enjoyed reading about Napoleon and Oliver Cromwell.[53] He felt that "truly successful men" were those with their own libraries.[54]

Pennsylvania

Brown left Hudson, Ohio, where he had a successful tannery, to be better situated to operate a safe and productive Underground Railroad station.[55][56] He moved to Richmond Township in Crawford County, Pennsylvania, in 1825[55][56][d] and lived there until 1835,[57] longer than he did anywhere else.[58] He bought 200 acres (81 hectares) of land, cleared an eighth of it, and quickly built a cabin, a two-story tannery with 18 vats, and a barn; in the latter was a secret, well-ventilated room to hide escaping slaves.[55][56] He transported refugees across the state border into New York and to an important Underground Railroad connection in Jamestown,[57] about 55 miles (89 km) from Richmond Township.[59] The escapees were hidden in the wagon he used to move the mail, hides for his tannery, and survey equipment.[57] For ten years, his farm was an important stop on the Underground Railroad,[60] during which, it is estimated to have helped 2,500 enslaved people on their journey to Canada, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development.[60] Brown recruited other Underground Railroad stationmasters to strengthen the network.[57]

Brown made money surveying new roads. He was involved in erecting a school, which first met in his home—he was its first teacher[61]—, and attracting a preacher[62][63] for a Congregational Society in Richmond. Their first meetings were held at the farm and tannery compound.[64] He also helped to establish a post office, and in 1828 President John Quincy Adams named him the first postmaster of Randolph Township, Pennsylvania; he was reappointed by President Andrew Jackson, serving until he left Pennsylvania in 1835.[62][65] He carried the mail for some years from Meadville, Pennsylvania, through Randolph to Riceville, some 20 miles (32 km).[66] He paid a fine at Meadville for declining to serve in the militia. During this period, Brown operated an interstate cattle and leather business along with a kinsman, Seth Thompson, from eastern Ohio.[66] In 1829, some white families asked Brown to help them drive off Native Americans who hunted annually in the area. Calling it a mean act, Brown declined, even saying "I would sooner take my gun and help drive you out of the country."[67][68]

In 1831, Brown's son Frederick (I) died, at the age of 4. Brown fell ill, and his businesses began to suffer, leaving him in severe debt. In mid-1832, shortly after the death of a newborn son, his wife Dianthe also died, either in childbirth or as an immediate consequence of it.[69] He was left with the children John Jr., Jason, Owen, Ruth and Frederick (II).[70][e] On July 14, 1833, Brown married 17-year-old Mary Ann Day (1817–1884), originally from Washington County, New York;[72] she was the younger sister of Brown's housekeeper at the time.[73] They eventually had 13 children,[74][75] seven of whom were sons who worked with their father in the fight to abolish slavery.[76]

Back to Ohio

In 1836, Brown moved his family from Pennsylvania to Franklin Mills, Ohio, where he taught Sunday school.[77] He borrowed heavily to buy land in the area, including property along canals being built, and entered into a partnership with Zenas Kent to construct a tannery along the Cuyahoga River, though Brown left the partnership before the tannery was completed.[78][79] Brown continued to work on the Underground Railroad.[57]

Brown became a bank director and was estimated to be worth US$20,000 (equivalent to about $590,710 in 2023).[80] Like many businessmen in Ohio, he invested too heavily in credit and state bonds and suffered great financial losses in the Panic of 1837. In one episode of property loss, Brown was jailed when he attempted to retain ownership of a farm by occupying it against the claims of the new owner.[81]

In November 1837, Elijah Parish Lovejoy was murdered in Alton, Illinois, for printing an abolitionist newspaper. Brown, deeply upset about the incident, became more militant in his behavior, comparable with Reverend Henry Highland Garnet.[57] Brown publicly vowed after the incident: "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!"[82] Brown objected to Black congregants being relegated to the balcony at his church[57] in Franklin Mills. According to daughter Ruth Brown's husband Henry Thompson, whose brother was killed at Harpers Ferry:

[H]e and his three sons, John, Jason, and Owen, were expelled from the Congregational church at Kent, then called Franklin, Ohio, for taking a colored man into their own pew; and the deacons of the church tried to persuade him to concede his error. My wife and various members of the family afterward joined the Wesley Methodists, but John Brown never connected himself with any church again.[42]

For three or four years he seemed to flounder hopelessly, moving from one activity to another without plan. He tried many different business efforts attempting to get out of debt. He bred horses briefly, but gave it up when he learned that buyers were using them as race horses.[83] He did some surveying, farming, and tanning.[84] Brown declared bankruptcy in federal court on September 28, 1842.[43] In 1843, three of his children — Charles, Peter, Austin — died of dysentery.[70]

From the mid-1840s, Brown had built a reputation as an expert in fine sheep and wool. For about one year, he ran Captain Oviatt's farm,[83] and he then entered into a partnership with Colonel Simon Perkins of Akron, Ohio, whose flocks and farms were managed by Brown and his sons.[85][f] Brown eventually moved into a home with his family across the street from the Perkins Stone Mansion.[86]

Springfield, Massachusetts

In 1846, Brown moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, as an agent for Ohio wool growers in their relations with New England manufacturers of woolen goods, but "also as a means of developing his scheme of emancipation".[88] The white leadership there, including "the publisher of The Republican, one of the nation's most influential newspapers, were deeply involved and emotionally invested in the anti-slavery movement".[89]

Brown made connections in Springfield that later yielded financial support he received from New England's great merchants, allowed him to hear and meet nationally famous abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, and included, after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the foundation of the League of Gileadites.[88][89] Brown's personal attitudes evolved in Springfield, as he observed the success of the city's Underground Railroad and made his first venture into militant, anti-slavery community organizing. In speeches, he pointed to the martyrs Elijah Lovejoy and Charles Turner Torrey as white people "ready to help blacks challenge slave-catchers".[90] In Springfield, Brown found a city that shared his own anti-slavery passions, and each seemed to educate the other. Certainly, with both successes and failures, Brown's Springfield years were a transformative period of his life that catalyzed many of his later actions.[89]

Two years before Brown's arrival in Springfield, in 1844, the city's African-American abolitionists had founded the Sanford Street Free Church, now known as St. John's Congregational Church, which became one of the most prominent abolitionist platforms in the United States. From 1846 until he left Springfield in 1850, Brown was a member of the Free Church, where he witnessed abolitionist lectures by the likes of Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth.[91] In 1847, after speaking at the Free Church, Douglass spent a night speaking with Brown, after which Douglass wrote, "From this night spent with John Brown in Springfield, Mass. [in] 1847, while I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful for its peaceful abolition."[89]

During Brown's time in Springfield, he became deeply involved in transforming the city into a major center of abolitionism, and one of the safest and most significant stops on the Underground Railroad.[92] Brown contributed to the 1848 republication, by his friend Henry Highland Garnet, of David Walker's An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829),[93] which he helped publicize.[94]

Before Brown left Springfield in 1850, the United States passed the Fugitive Slave Act, a law mandating that authorities in free states aid in the return of escaped slaves and imposing penalties on those who aid in their escape. In response, Brown founded a militant group to prevent the recapture of fugitives, the League of Gileadites,[93][g] operated by free Blacks—like the "strong-minded, brave, and dedicated" Eli Baptist, William Montague, and Thomas Thomas[89][h]—who risked being caught by slave catchers and sold into slavery.[57] Upon leaving Springfield in 1850, he instructed the League to act "quickly, quietly, and efficiently" to protect slaves that escaped to Springfield – words that would foreshadow Brown's later actions preceding Harpers Ferry.[95] From Brown's founding of the League of Gileadites onward, not one person was ever taken back into slavery from Springfield.[89]

His daughter Amelia died in 1846, followed by Emma in 1849.[85]

New York

In 1848, bankrupt and having lost the family's house, Brown heard of Gerrit Smith's Adirondack land grants to poor black men, in so remote a location that Brown later called it Timbuctoo, and decided to move his family there to establish a farm where he could provide guidance and assistance to the blacks who were attempting to establish farms in the area.[96] He bought from Smith land in the town of North Elba, New York (near Lake Placid), for $1 an acre ($2/ha).[97] It has a magnificent view[14] and has been called "the highest arable spot of land in the State."[98] After living with his family about two years in a small rented house, and returning for several years to Ohio, he had the current house – now a monument preserved by New York State – built for his family, viewing it as a place of refuge for them while he was away. According to youngest son Salmon, "frugality was observed from a moral standpoint, but one and all we were a well-fed, well-clad lot."[99]

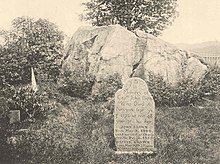

After he was executed on December 2, 1859, his widow took his body there for burial; the trip took five days, and he was buried on December 8. Watson's body was located and buried there in 1882. In 1899 the remains of 12 of Brown's other collaborators, including his son Oliver, were located and brought to North Elba. They could not be identified well enough for separate burials, so they are buried together in a single casket donated by the town of North Elba; there is a collective plaque there now. Since 1895, the John Brown Farm State Historic Site has been owned by New York State and is now a National Historic Landmark.[96]

Actions in Kansas

Kansas Territory was in the midst of a state-level civil war from 1854 to 1860, referred to as the Bleeding Kansas period, between pro- and anti-slavery forces.[100] From 1854 to 1856, there had been eight killings in Kansas Territory attributable to slavery politics. There had been no organized action by abolitionists against pro-slavery forces by 1856.[101] The issue was to be decided by the voters of Kansas, but who these voters were was not clear; there was widespread voting fraud in favor of the pro-slavery forces, as a Congressional investigation confirmed.[100]

Move to Kansas

Five of Brown's sons — John Jr., Jason, Owen, Frederick, and Salmon — moved to Kansas Territory in the spring of 1855. Brown, his son Oliver, and his son-in-law Henry Thompson followed later that year[102] with a wagon loaded with weapons and ammunition.[103][i] Brown stayed with Florella (Brown) Adair and the Reverend Samuel Adair, his half-sister and her husband, who lived near Osawatomie. During that time, he rallied support to fight proslavery forces,[102] and became the leader of the antislavery forces in Kansas.[103][105]

Pottawatomie

Brown and the free-state settlers intended to bring Kansas into the union as a slavery-free state.[106] After the winter snows thawed in 1856, the pro-slavery activists began a campaign to seize Kansas on their own terms. Brown was particularly affected by the sacking of Lawrence, the center of anti-slavery activity in Kansas, on May 21, 1856. A sheriff-led posse from Lecompton, the center of pro-slavery activity in Kansas, destroyed two abolitionist newspapers and the Free State Hotel. Only one man, a border ruffian, was killed.[107]

Preston Brooks's May 22 caning of anti-slavery Senator Charles Sumner in the United States Senate, news of which arrived by newswire (telegraph), also fueled Brown's anger. A pro-slavery writer, Benjamin Franklin Stringfellow, of the Squatter Sovereign, wrote that "[pro-slavery forces] are determined to repel this Northern invasion, and make Kansas a slave state; though our rivers should be covered with the blood of their victims, and the carcasses of the abolitionists should be so numerous in the territory as to breed disease and sickness, we will not be deterred from our purpose".[107] Brown was outraged by both the violence of the pro-slavery forces and what he saw as a weak and cowardly response by the antislavery partisans and the Free State settlers, whom he described as "cowards, or worse".[108]

The Pottawatomie massacre occurred during the night of May 24 and the morning of May 25, 1856. Under Brown's supervision, his sons and other abolitionist settlers took from their residences and killed five "professional slave hunters and militant pro-slavery" settlers.[109] The massacre was the match in the powderkeg that precipitated the bloodiest period in "Bleeding Kansas" history, a three-month period of retaliatory raids and battles in which 29 people died.[101]

Henry Clay Pate, who was part of the sacking of Lawrence, was, either during or shortly before, commissioned as a Deputy United States Marshal.[110] On hearing news of John Brown's actions at the Pottawatomie Massacre, Pate set out with a band of thirty men to hunt Brown down.[111] During the hunt for Brown, two of his sons (Jason and John Junior) were captured (either by Pate or another marshal), charged with murder, and thrown in irons.[110][111] Brown and free-state militia gathered to confront Pate. Two of Pate's men were captured, which led to the conflict on June 2.[112]

Palmyra and Osawatomie

In the Battle of Black Jack of June 2, 1856, John Brown, nine of his followers, and 20 local men successfully defended a Free State settlement at Palmyra, Kansas, against an attack by Henry Clay Pate. Pate and 22 of his men were taken prisoner.[113]

In August, a company of over 300 Missourians under the command of General John W. Reid crossed into Kansas and headed toward Osawatomie, intending to destroy the Free State settlements there and then march on Topeka and Lawrence.[114] On the morning of August 30, 1856, they shot and killed Brown's son Frederick and his neighbor David Garrison on the outskirts of Osawatomie. Brown, outnumbered more than seven to one, arranged his 38 men behind natural defenses along the road. Firing from cover, they managed to kill at least 20 of Reid's men and wounded 40 more.[115] Reid regrouped, ordering his men to dismount and charge into the woods. Brown's small group scattered and fled across the Marais des Cygnes River. One of Brown's men was killed during the retreat and four were captured. While Brown and his surviving men hid in the woods nearby, the Missourians plundered and burned Osawatomie. Though defeated, Brown's bravery and military shrewdness in the face of overwhelming odds brought him national attention and made him a hero to many Northern abolitionists.[116]

On September 7, Brown entered Lawrence to meet with Free State leaders and help fortify against a feared assault. At least 2,700 pro-slavery Missourians were once again invading Kansas. On September 14, they skirmished near Lawrence. Brown prepared for battle, but serious violence was averted when the new governor of Kansas, John W. Geary, ordered the warring parties to disarm and disband, and offered clemency to former fighters on both sides.[117]

Brown had become infamous and federal warrants were issued for his arrest due to his actions in Kansas. He became careful of how he travelled and whom he stayed with across the country.[118]

Raid at Harpers Ferry

Brown's plans

Brown's plans for a major attack on American slavery began long before the raid. According to his wife Mary, interviewed while her husband was awaiting his execution, Brown had been planning the attack for 20 years.[119] Frederick Douglass noted that he made the plans before he fought in Kansas.[120] For instance, he spent the years between 1842 and 1849 settling his business affairs, moving his family to the Negro community at Timbuctoo, New York, and organizing in his own mind an anti-slavery raid that would strike a significant blow against the entire slave system, running slaves off Southern plantations.[121]

According to his first biographer James Redpath, "for thirty years, he secretly cherished the idea of being the leader of a servile insurrection: the American Moses, predestined by Omnipotence to lead the servile nations in our Southern States to freedom."[122] An acquaintance said: "As Moses was raised up and chosen of God to deliver the Children of Israel out of Egyptian bondage, ...he was...fully convinced in his own mind that he was to be the instrument in the hands of God to effect the emancipation of the slaves."[123]

Brown said that,

A few men in the right, and knowing that they are right, can overturn a mighty king. Fifty men, twenty men, in the Alleghenies would break slavery to pieces in two years.[124]

Brown kept his plans a secret, including the care he took not to share the plans with his men, according to Jeremiah Anderson, one of the participants in the raid.[125] His son Owen, the only one who survived of Brown's three participating sons, said in 1873 that he did not think his father wrote down the entire plan.[126] He did discuss his plans at length, for over a day, with Frederick Douglass, trying unsuccessfully to persuade Douglass, a black leader, to accompany him to Harpers Ferry (which Douglass thought a suicidal mission that could not succeed).[127]

Preparations

Financial and political backing

To attain financial backing and political support for the raid on Harpers Ferry, Brown spent most of 1857 meeting with abolitionists in Massachusetts, New York, and Connecticut.[128] Initially Brown returned to Springfield, where he received contributions, and also a letter of recommendation from a prominent and wealthy merchant, George Walker. Walker was the brother-in-law of Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, the secretary for the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee, who introduced Brown to several influential abolitionists in the Boston area in January 1857.[88][129] Amos Adams Lawrence, a prominent Boston merchant, secretly gave Brown a large amount of cash.[130] William Lloyd Garrison, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker and George Luther Stearns, and Samuel Gridley Howe also supported Brown,[130] although Garrison, a pacificist, disagreed about the need to use violence to end slavery.[131]

Most of the money for the raid came from the "Secret Six",[128][132] Franklin B. Sanborn, Samuel G. Howe M.D., businessman George L. Stearns, real estate tycoon Gerrit Smith, transcendentalist and reforming minister of the Unitarian church Theodore Parker, and Unitarian minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson.[128] Recent research has also highlighted the substantial contribution of Mary Ellen Pleasant, an African American entrepreneur and abolitionist, who donated $30,000 (equivalent to $981,000 in 2023) toward the cause.[133]

In Boston, he met Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[131] Even with the Secret Six and other contributors, Brown had not collected all money needed to fund the raid. He wrote an appeal, Old Browns Farewell, to abolitionists in the east with some success.[131]

In December 1857, an anti-slavery Mock Legislature, organized by Brown, met in Springdale, Iowa.[134] On several of Brown's trips across Iowa he preached at Hitchcock House, an Underground Railroad stop in Lewis, Iowa.[135]

"Virginia scheme"

With a free-state victory in the October elections, Kansas was quiet. Brown made his men return to Iowa, where he told them tidbits of his Virginia scheme.[136] In January 1858, Brown left his men in Springdale, Iowa, and set off to visit Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York. There he discussed his plans with Douglass, and reconsidered Forbes' criticisms.[137] Brown wrote a Provisional Constitution that would create a government for a new state in the region of his invasion. He then traveled to Peterboro, New York, and Boston to discuss matters with the Secret Six. In letters to them, he indicated that, along with recruits, he would go into the South equipped with weapons to do "Kansas work".[138] While in Boston making secret preparations for his operation on Harper's Ferry, he was raising money for weapons that were manufactured in Connecticut. Abolitionist Chaplain Photius Fisk gave him a sizable donation and obtained his autograph which he later gave to the Kansas Historical Society.[139]

Brown started to wear a beard, "to change his usual appearance".[140]

Weapons

The Massachusetts Committee pledged to provide 200 Sharps Rifles and ammunition, which were being stored at Tabor, Iowa. The rifles were originally intended for use by free-staters in Kansas. After negotiation between the officers of the Massachusetts Kansas Committee and the National Committee, the rifles were transferred to the Massachusetts Committee for use in the Harpers Ferry raid.[141] Horatio N. Rust, a friend of Brown's, helped acquire for 1,000 pikes for the intended slave rebellion.[142]

Weapons were purchased and sent to Kennedy Farmhouse in Sharpsburg, Maryland, where they were stored.[143] Brown's plan was to make use of weapons, ammunition, and other military equipment stored at the armory, arsenal, and the rifle factory in Harpers Ferry.[144] There were an estimated 100,000 muskets and rifles at the armory and arsenal complex at the time.[145]

The more sophisticated weapons, like Sharps rifles and pistols, were to be used by Black and White officers. The remaining fighters would use spear-like pikes, shotguns, and muskets.[146]

Constitutional convention in Ontario

Brown and 12 of his followers, including his son Owen, traveled to Chatham, Ontario, where he convened on May 10 a Constitutional Convention.[147] The convention, with several dozen delegates including his friend James Madison Bell, was put together with the help of Dr. Martin Delany.[148] One-third of Chatham's 6,000 residents were fugitive slaves, and it was here that Brown was introduced to Harriet Tubman, who helped him recruit.[149] The convention's 34 blacks and 12 whites adopted Brown's Provisional Constitution. Brown had long used the terminology of the Subterranean Pass Way from the late 1840s, so it is possible that Delany conflated Brown's statements over the years. Regardless, Brown was elected commander-in-chief and named John Henrie Kagi his "Secretary of War". Richard Realf was named "Secretary of State". Elder Monroe, a black minister, was to act as president until another was chosen. A. M. Chapman was the acting vice president; Delany, the corresponding secretary. In 1859, "A Declaration of Liberty by the Representatives of the Slave Population of the United States of America" was written.[150][151]

Crisis

While in New York City, Brown was introduced to Hugh Forbes, an English mercenary, who had experience as a military tactician fighting with Giuseppe Garibaldi. Concerned about Brown's strategy, Forbes undermined and delayed the plans for the raid.[152]

Although nearly all of the delegates signed the constitution, few volunteered to join Brown's forces, although it will never be clear how many Canadian expatriates actually intended to join Brown because of a subsequent "security leak" that threw off plans for the raid, creating a hiatus in which Brown lost contact with many of the Canadian leaders. This crisis occurred when Hugh Forbes, Brown's mercenary, tried to expose the plans to Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson and others. The Secret Six feared their names would be made public. Howe and Higginson wanted no delays in Brown's progress, while Parker, Stearns, Smith and Sanborn insisted on postponement. Stearns and Smith were the major sources of funds, and their words carried more weight. To throw Forbes off the trail and invalidate his assertions, Brown returned to Kansas in June, and remained in that vicinity for six months. There he joined forces with James Montgomery, who was leading raids into Missouri.

Continue to organize funds and forces

On December 20, Brown led his own raid, in which he liberated 11 slaves, took captive two white men, and looted horses and wagons. The Governor of Missouri announced a reward of $3,000 (equivalent to $101,733 in 2023) for his capture. On January 20, 1859, he embarked on a lengthy journey to take the liberated slaves to Detroit and then on a ferry to Canada. While passing through Chicago, Brown met with abolitionists Allan Pinkerton, John Jones, and Henry O. Wagoner who arranged and raised the fare for the passage to Detroit[153] and purchased supplies for Brown. Jones's wife and fellow abolitionist, Mary Jane Richardson Jones, provided new clothes for Brown and his men, including the garb Brown was hanged in six months later.[154][155] On March 12, 1859, Brown met with Frederick Douglass and Detroit abolitionists George DeBaptiste, William Lambert, and others at William Webb's house in Detroit to discuss emancipation.[156] DeBaptiste proposed that conspirators blow up some of the South's largest churches. The suggestion was opposed by Brown, who felt humanity precluded such unnecessary bloodshed.[157]

Over the course of the next few months, he traveled again through Ohio, New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts to drum up more support for the cause. On May 9, he delivered a lecture in Concord, Massachusetts, that Amos Bronson Alcott, Emerson, and Thoreau attended. Brown reconnoitered with the Secret Six.[158]

As he began recruiting supporters for an attack on slaveholders, Brown was joined by Harriet Tubman, "General Tubman", as he called her.[159] Her knowledge of support networks and resources in the border states of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware was invaluable to Brown and his planners.[160] She also raised funds for Brown.[161]

Some abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, opposed his tactics, but Brown dreamed of fighting to create a new state for freed slaves and made preparations for military action. After he began the first battle, he believed, slaves would rise up and carry out a rebellion across the South.[160]

Brown's forces

The men that fought with Brown in Kansas gathered at Springdale, Iowa, a Quaker settlement, about January 1858, to prepare to execute Brown's Virginia scheme.[162]

In June, Brown paid his last visit to his family in North Elba before departing for Harpers Ferry. He stayed one night en route in Hagerstown, Maryland, at the Washington House, on West Washington Street. On June 30, 1859, the hotel had at least 25 guests, including I. Smith and Sons, Oliver Smith and Owen Smith, and Jeremiah Anderson, all from New York. From papers found in the Kennedy Farmhouse after the raid, it is known that Brown wrote to Kagi that he would sign into a hotel as I. Smith and Sons.[158]

The men who prepared for the raid at Kennedy Farmhouse and participated in the raid with Brown included two groups of men:

- A group that fought with him in Kansas and gathered at Springdale, Iowa, to prepare and drill for the raid,[163]

- Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson, 26, born in Indiana, served with Brown in Kansas, killed in the raid.[164]

- Oliver Brown, 20, John Brown's son, served in Kansas. He was mortally wounded during the raid.[165]

- Owen Brown, about 35, John Brown's son, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid.[166]

- John E. Cook, 29, reformer and former soldier, attended Oberlin College, he initially escaped capture, but was found and hanged.[166]

- Albert Hazlett, 23, fought in Kansas, escaped following the raid, but was captured and hanged.[167]

- John Henry Kagi, about 24, a teacher, became Brown's second in command. Before the raid he printed copies of Brown's constitution in a printing shop he established in Hamilton, Ontario. He was mortally wounded during the raid.[168]

- William H. Leeman, 20, fought with the free-staters in Kansas for three years, beginning at the age of 17. He died during the raid.[169]

- Aaron Dwight Stevens, about 28, was a former soldier and fighter in Kansas, who gave the men military training and drills. He was wounded during the raid, after which he was executed.[170]

- Charles Plummer Tidd, 25, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid and later served during the Civil War.[170]

- Men he met when rounding up recruits for the raid:[163]

- Watson Brown, son of John Brown, mortally wounded during the raid.[171]

- John Anthony Copeland Jr. was a free black man who joined John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. He was captured during the raid and was executed.[172]

- Barclay Coppoc, 19, escaped capture following the raid. He fought in the Civil War.[173]

- Edwin Coppoc, 24, captured and hanged.[174]

- Shields Green, about 23, escaped slavery, captured and hanged.[167]

- Lewis Sheridan Leary, a harness maker freed by his white father, mortally wounded during the raid.[175]

- Francis Jackson Meriam, 22, grandson of Francis Jackson who was a leader of Antislavery Societies. Meriam was an aristocrat. He escaped during the raid. Meriam led an African American infantry group during the Civil War.[167]

- Dangerfield Newby, 44, born a slave, escaped slavery, returned to Virginia to fight in the raid, where he was killed.[176]

- Stewart Taylor, 23, a wagonmaker from Canada, mortally wounded during the raid.[177]

- Dauphin Thompson, 21, married to Ruth Brown, John Brown's daughter, mortally wounded during the raid.[177]

- William Thompson, 26, mortally wounded during the raid.[177]

They were at Kennedy Farmhouse, four to five miles away from Harpers Ferry. Brown's daughter and daughter-in-law, Anne and Martha, Oliver's wife, prepared food and kept the house for the men from August and throughout the month of September.[143]

The raid

Brown led his forces for Harper Ferry on the night of October 16, 1859.[178] The objective was to take the armory, the arsenal, the town, and then the rifle factory. Then, they wanted to free all the slaves in Harpers Ferry.[179] After that, they would move south with those newly freed people who wanted to join the fight to free other enslaved people.[180] Brown told his men to take prisoners who disobeyed them and to fight only in self-defense.[181]

Initially, they met no resistance entering the town. John Brown's raiders cut the telegraph wires and easily captured the armory, which was being defended by a single watchman. They next rounded up hostages from nearby farms, including Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington. They also spread the news to the local slaves that their liberation was at hand.[182]

When an eastbound Baltimore and Ohio Railroad train approached the town, Brown held it and then inexplicably allowed it to continue on its way. At the next station where the telegraph still worked, the conductor sent a telegram to B&O headquarters in Baltimore. The railroad sent telegrams to President Buchanan and Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise.[183]

By the morning of October 18 the engine house, later known as John Brown's Fort, was surrounded by a company of U.S. Marines under the command of First Lieutenant Israel Greene, USMC, with Colonel Robert E. Lee of the United States Army in overall command.[184]

Army First Lieutenant J. E. B. Stuart approached the engine-house to apprehend Brown and told the raiders their lives would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused, saying, "No, I prefer to die here." Stuart then gave a signal and the Marines used sledgehammers and a makeshift battering ram to break down the engine room door. Lieutenant Israel Greene cornered Brown and struck him several times, wounding his head. In three minutes, Brown and the survivors were captives.[185]

Altogether, Brown's men killed four townspeople and one Marine. Ten people were wounded, one of whom was a Marine.[186] Four of Brown's men were not captured, the rest died during the raid or were captured and executed.[163] Among the raiders killed were John Henry Kagi, Lewis Sheridan Leary, and Dangerfield Newby; those hanged besides Brown included John Copeland, Edwin Coppock, Aaron Stevens, and Shields Green.[187][188] Most of the enslaved people were returned to their slaveholders, while some were able to escape capture. A man named Phil was captured with Brown, and a man named Jim drowned in the Shenandoah.[189]

Brown and the others captured were held in the office of the armory. On October 18, 1859, Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise, Virginia Senator James M. Mason, and Representative Clement Vallandigham of Ohio arrived in Harpers Ferry. Brown conceded that he did not receive the support he expected from White and Black people. The questioning lasted several hours.[190]

The trial

Brown was charged with treason and tried in a Virginia state court at Governor Wise's request. Accordingly, the charge was treason against Virginia.[191] President Buchanan did not object.[192]

The answer provided in 1859 was more political ~ than legal. The president of the United States and the governor of Virginia decided that Brown would be tried in Virginia for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, and that is where he was tried. This decision thrust Virginia rather than the United States into the role of the offended sovereign and contributed incalculably to the widening abyss between North and South. John Brown was condemned not as an enemy of the American people but as an enemy of Virginia and, by logical extension, of Southern slaveholders.

— Brian McGinty, author of John Brown's Trial[193]

Brown was tried with his men who had lived through the raid and had not escaped — Copeland, Coppoc, Green, and Stevens — on charges of murder, "conspiracy to foment a slave insurrection", and treason, as of October 26.[194]

On November 2, after a week-long trial in Charles Town, the county seat of Jefferson County,[195][196] and 45 minutes of deliberation, the jury found Brown guilty on all three counts.[196] He was sentenced to be hanged in public on December 2.[196] He was the first person executed for treason in the history of the United States.[11][12]

The trial attracted reporters who were able to send their articles via the new telegraph. They were reprinted in numerous papers. It was the first trial in the U.S. to be nationally reported.[197]

November 2 to December 2, 1859

Before his conviction, reporters were not allowed access to Brown, as the judge and Andrew Hunter feared that his statements, if quickly published, would exacerbate tensions, especially among the enslaved. This was much to Brown's frustration, as he stated that he wanted to make a full statement of his motives and intentions through the press.[198] Once he had been convicted, the restriction was lifted, and, glad for the publicity, he talked with reporters and anyone else who wanted to see him, except pro-slavery clergy.[71] Brown received more letters than he ever had in his life. He wrote replies constantly, hundreds of eloquent letters, often published in newspapers.[199]

Rescue and Victor Hugo's pardon plans

There were well-documented and specific plans to rescue Brown, as Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise wrote to President Buchanan. Throughout the weeks Brown and six of his collaborators were in the Jefferson County Jail in Charles Town, the town was filled with various types of troops and militia, hundreds and sometimes thousands of them. Brown's trips from the jail to the courthouse and back, and especially the short trip from the jail to the gallows, were heavily guarded. Wise halted all non-military transportation on the Winchester and Potomac Railroad (from Maryland south through Harpers Ferry to Charles Town and Winchester), from the day before through the day after the execution. Jefferson County was under martial law,[200] and the military orders in Charles Town for the execution day had 14 points.[201]

However, Brown said several times that he did not want to be rescued. He refused the assistance of Silas Soule, a friend from Kansas who infiltrated the Jefferson County Jail one day by getting himself arrested for drunken brawling and offered to break him out during the night and flee northward to New York State and possibly Canada. Brown told Silas that, aged 59, he was too old to live a life on the run from the federal authorities as a fugitive and wanted to accept his execution as a martyr for the abolitionist cause. As Brown wrote his wife and children from jail, he believed that his "blood will do vastly more towards advancing the cause I have earnestly endeavoured to promote, than all I have done in my life before."[202] "I am worth inconceivably more to hang than for any other purpose."[203]

Victor Hugo, from exile on Guernsey, tried to obtain a pardon for John Brown: he sent an open letter that was published by the press on both sides of the Atlantic. This text, written at Hauteville House on December 2, 1859, warned of a possible civil war:

Politically speaking, the murder of John Brown would be an uncorrectable sin. It would create in the Union a latent fissure that would in the long run dislocate it. Brown's agony might perhaps consolidate slavery in Virginia, but it would certainly shake the whole American democracy. You save your shame, but you kill your glory. Morally speaking, it seems a part of the human light would put itself out, that the very notion of justice and injustice would hide itself in darkness, on that day where one would see the assassination of Emancipation by Liberty itself.

The letter was initially published in the London News[dubious – discuss] and was widely reprinted. After Brown's execution, Hugo wrote a number of additional letters about Brown and the abolitionist cause.[204]

Abolitionists in the United States saw Hugo's writings as evidence of international support for the anti-slavery cause. The most widely publicized commentary on Brown to reach America from Europe was an 1861 pamphlet, John Brown par Victor Hugo, that included a brief biography and reprinted two letters by Hugo, including that of December 9, 1859. The pamphlet's frontispiece was an engraving of a hanged man by Hugo that became widely associated with the execution.[205]

Last words, death and aftermath

On December 1, 1859, Mary Ann Brown, who had stayed away from the prison due to Brown's concern for her safety, visited her husband for several hours with permission from Governor Wise.[206]

On the day of his execution, December 2,[207] Brown read his Bible and wrote a final letter to his wife, which included the will he had written the previous day,[208][206][209] as large meetings were held in many cities in the Northeast. In many of the cases, "Negroes were the chief actors in creating excitement".[207]

Brown was well read and knew that the last words of prominent people are valued. That morning, Brown wrote and gave to his jailor Avis the words he wanted to be remembered by:

I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.[210]

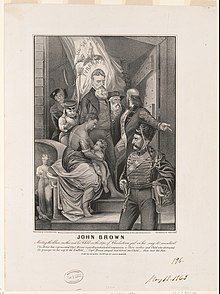

At 11:00 a.m. Brown rode, sitting on his coffin in a furniture wagon, from the county jail through a crowd of 2,000 soldiers to a small field a few blocks away, where the gallows were.[208] The military, prepared for an attack, lined the square where Brown was to be hanged, with "the greatest array of disciplined forces ever seen in Virginia", according to Major Preston.[206] Among the soldiers in the crowd were future Confederate general Stonewall Jackson, and John Wilkes Booth (the latter borrowing a militia uniform to gain admission to the execution).[208]

Brown, who did not want to have a minister with him, displayed "the most complete fearlessness of & insensibility to danger & death" as he walked to the gallows.[206] Brown was hanged at 11:15 a.m. and was pronounced dead 35 minutes later by the coroner.[211]

The poet Walt Whitman, in Year of Meteors, described viewing the execution.[212]

Funeral and burial

Brown's desire, as told to the jailor in Charles Town, was that his body be burned, "the ashes urned", and his dead sons disinterred and treated likewise.[213][214] He wanted his epitaph to be:

- I have fought a good fight.

- I have finished my course.

- I have kept the faith. [2 Timothy 4:7][215]

However, according to the sheriff of Jefferson County, Virginia law did not allow the burning of bodies, and Mrs. Brown did not want it. Brown's body was placed in a wooden coffin with the noose still around his neck, and the coffin was then put on a train to take it away from Virginia to his family homestead in North Elba, New York for burial.[216]

His body needed to be prepared for burial; this was supposed to take place in Philadelphia. There were many Southern pro-slavery medical students and faculty in Philadelphia, and as a direct result, they left the city en masse on December 21, 1859, for Southern medical schools, never to return. When Mary and her husband's body arrived on December 3, Philadelphia Mayor Alexander Henry met the train, with many policemen, and said public order could not be maintained if the casket remained in Philadelphia. In fact he "made a fake casket, covered with flowers and flags[,] which was carefully lifted from the coach"; the crowd followed the sham casket. The genuine casket was immediately sent onwards.[217][218] It was transported through places special to Brown during his life. His corpse was transported via Troy, New York, Rutland, Vermont, and across Lake Champlain by boat. His corpse arrived at the Brown farm at North Elba, New York.[219] Brown's body was washed, dressed, and placed, with difficulty, in a 5-foot-10-inch (1.78 m) walnut coffin, in New York.[220] He was buried on December 8, 1859.[221] Abolitionist Rev. Joshua Young gave a prayer, and James Miller McKim and Wendell Phillips spoke.[219][221]

In the North, large memorial meetings took place, church bells rang, minute guns were fired, and famous writers such as Emerson and Thoreau joined many Northerners in praising Brown.[222]

On July 4, 1860, family and admirers of Brown gathered at his farm for a memorial. This was the last time that the surviving members of Brown's family gathered together. The farm was sold, except for the burial plot. By 1882, John Jr., Owen, Jason, and Ruth, widow of Henry Thompson, lived in Ohio; his wife and their two unmarried daughters in California.[223] By 1886, Owen, Jason, and Ruth were living near Pasadena, California, where they were honored in a parade.[224]

Senate investigation

On December 14, 1859, the U.S. Senate appointed a bipartisan committee to investigate the Harpers Ferry raid and to determine whether any citizens contributed arms, ammunition or money to John Brown's men. The Democrats attempted to implicate the Republicans in the raid; the Republicans tried to disassociate themselves from Brown and his acts.[225][226]

The Senate committee heard testimony from 32 witnesses, including Liam Dodson, one of the surviving abolitionists. The report, authored by chairman James Murray Mason, a pro-slavery Democrat from Virginia, was published in June 1860. It found no direct evidence of a conspiracy, but implied that the raid was a result of Republican doctrines.[226] The two committee Republicans published a minority report, but were apparently more concerned about denying Northern culpability than clarifying the nature of Brown's efforts. Republicans such as Abraham Lincoln rejected any connection with the raid, calling Brown "insane".[227]

The investigation was performed in a tense environment in both houses of Congress. One senator wrote to his wife that "The members on both sides are mostly armed with deadly weapons and it is said that the friends of each are armed in the galleries." After a heated exchange of insults, a Mississippian attacked Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania with a Bowie knife in the House of Representatives. Stevens' friends prevented a fight.[228]

The Senate committee was very cautious in its questions of two of Brown's backers, Samuel Howe and George Stearns, out of fear of stoking violence. Howe and Stearns later said that the questions were asked in a manner that permitted them to give honest answers without implicating themselves.[228] Civil War historian James M. McPherson stated that "A historian reading their testimony, however, will be convinced that they told several falsehoods."[229]

Aftermath of the raid

John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry was among the last in a series of events that led to the American Civil War.[230] Southern slaveowners, hearing initial reports that hundreds of abolitionists were involved, were relieved the effort was so small, but feared other abolitionists would emulate Brown and attempt to lead slave rebellions.[231] Future Confederate President Jefferson Davis feared "thousands of John Browns".[232] Therefore, the South reorganized the decrepit militia system. These militias, well-established by 1861, became a ready-made Confederate army, making the South better prepared for war.[233]

Southern Democrats charged that Brown's raid was an inevitable consequence of the political platform of what they invariably called "the Black Republican Party". In light of the upcoming elections in November 1860, the Republicans tried to distance themselves as much as possible from Brown, condemning the raid and dismissing its leader as an insane fanatic. As one historian explains, Brown was successful in polarizing politics: "Brown's raid succeeded brilliantly. It drove a wedge through the already tentative and fragile Opposition–Republican coalition and helped to intensify the sectional polarization that soon tore the Democratic party and the Union apart."[233]

Many abolitionists in the North viewed Brown as a martyr, sacrificed for the sins of the nation. Immediately after the raid, William Lloyd Garrison published a column in The Liberator, judging Brown's raid "well-intended but sadly misguided" and "wild and futile".[234] However, he defended Brown's character from detractors in the Northern and Southern press and argued that those who supported the principles of the American Revolution could not consistently oppose Brown's raid. On the day Brown was hanged, Garrison reiterated the point in Boston: "whenever commenced, I cannot but wish success to all slave insurrections".[235]

Frederick Douglass believed that Brown's "zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine – it was as the burning sun to my taper light – mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him."[236]

Viewpoints

Contemporaries

Between 1859 and Lincoln's assassination in 1865, Brown was the most famous American: emblem to the North, as Wendell Phillips put it,[237] and traitor to the South. According to Frederick Douglass, "He was with the troops during that war, he was seen in every camp fire, and our boys pressed onward to victory and freedom, timing their feet to the stately stepping of Old John Brown as his soul went marching on."[238] Douglass called him "a brave and glorious old man. ...History has no better illustration of pure, disinterested benevolence."[239]

Other black leaders of the time—Martin Delany, Henry Highland Garnet, Harriet Tubman—also knew and respected Brown. "Tubman thought Brown was the greatest white man who ever lived",[240] and she said later he did more for American blacks than Lincoln did.[241]

Black businesses across the North closed on the day of his execution.[242] Church bells tolled across the North.[12] In response to the death sentence, Ralph Waldo Emerson remarked that "[John Brown] will make the gallows glorious like the Cross."[243] In 1863, Julia Ward Howe wrote the popular hymn the Battle Hymn of the Republic to the tune of John Brown's body, which included a line "As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free", comparing Brown's sacrifice to that of Jesus Christ.[12]

Lincoln thought Brown had “shown great courage, rare unselfishness.” But, with most Americans of the day, Lincoln believed Brown had gone too far. “Old John Brown has just been executed for treason against the state. We cannot object,” Lincoln reasoned, “even though he agreed with us in thinking slavery wrong."

According to W. E. B. Du Bois in his 1909 biography, John Brown. Brown's raid stood as "a great white light – an unwavering, unflickering brightness, blinding by its all-seeing brilliance, making the whole world simply a light and a darkness – a right and a wrong."[244]

According to his friend and financier, the rich abolitionist Gerrit Smith, "If I were asked to point out the man in all this world I think most truly a Christian, I would point to John Brown."[245][246]

Historians and other writers

Writers continue to vigorously debate Brown's personality, sanity, motivations, morality, and relation to abolitionism.[15] Once the Reconstruction era had ended, with the country distancing itself from the anti-slavery cause, and martial law imposed in the South, the historical view of Brown changed. Historian James Loewen surveyed American history textbooks prior to 1995 and noted that until about 1890, historians considered Brown perfectly sane, but from about 1890 until 1970, he was generally portrayed as insane.[247] Oswald Garrison Villard, the grandson of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, wrote a favorable 1910 biography of Brown, though it also added fuel to the anti-Brown fire by criticizing him as a muddled, pugnacious, bumbling, and homicidal madman.[15][248] Villard himself was a pacifist and admired Brown in many respects, but his interpretation of the facts provided a paradigm for later anti-Brown writers. Similarly, a 1923 textbook stated, "The farther we getaway from the excitement of 1859 the more we are disposed to consider this extraordinary man the victim of mental delusions."[249] In 1978, NYU historian Albert Fried concluded that historians who portrayed Brown as a dysfunctional figure are "really informing me of their predilections, their judgment of the historical event, their identification with the moderates and opposition to the 'extremists.'"[250] This view of Brown has come to prevail in academic writing and in journalism. Biographer Louis DeCaro Jr. wrote in 2007, "there is no consensus of fairness with respect to Brown in either the academy or the media."[251] Biographer Stephen B. Oates has described Brown as "maligned as a demented dreamer ... (but) in fact one of the most perceptive human beings of his generation".[252]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Some writers describe Brown as a monomaniacal zealot, others as a hero. In 1931, the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans erected a counter-monument, to Heyward Shepherd, a free black man who was the first fatality of the Harpers Ferry raid, claiming without evidence that he was a "representative of Negroes of the neighborhood, who would not take part".[253] By the mid-20th century, some scholars were fairly convinced that Brown was a fanatic and killer, while some African Americans sustained a positive view of him.[254] According to Stephen Oates, "unlike most Americans at his time, he had no racism. He treated blacks equally. ...He was a success, a tremendous success because he was a catalyst of the Civil War. He didn't cause it but he set fire to the fuse that led to the blow up."[255] Journalist Richard Owen Boyer considered Brown "an American who gave his life that millions of other Americans might be free", and others held similarly positive views.[256][257][258]

Some historians, such as Paul Finkelman, compare Brown to contemporary terrorists such as Osama bin Laden and Timothy McVeigh,[15][259][260] Finkelman calling him "simply part of a very violent world" and further stating that Brown "is a bad tactician, a bad strategist, he's a bad planner, he's not a very good general – but he's not crazy".[15] Historian James Gilbert labels Brown a terrorist by 21st-century criteria.[261] Gilbert writes: "Brown's deeds conform to contemporary definitions of terrorism, and his psychological predispositions are consistent with the terrorist model."[262] In contrast, biographer David S. Reynolds gives Brown credit for starting the Civil War or "killing slavery", and cautions others against identifying Brown with terrorism.[263] Reynolds saw Brown as inspiring the Civil Rights Movement a century later, adding "it is misleading to identify Brown with modern terrorists."[263][264] Malcolm X said that white people could not join his black nationalist Organization of Afro-American Unity, but "if John Brown were still alive, we might accept him".[265]

In his posthumous The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861 (1976), David Potter argued that the emotional effect of Brown's raid exceeded the philosophical effect of the Lincoln–Douglas debates, and reaffirmed a deep division between North and South.[265] Biographer Louis A. DeCaro Jr., who has debunked many historical allegations about Brown's early life and public career, concludes that although he "was hardly the only abolitionist to equate slavery with sin, his struggle against slavery was far more personal and religious than it was for many abolitionists, just as his respect and affection for black people was far more personal and religious than it was for most enemies of slavery".[266] Historian and Brown documentary scholar Louis Ruchames wrote: "Brown's action was one of great idealism and placed him in the company of the great liberators of mankind."[267]

Several 21st-century works about Brown are notable for the absence of hostility that characterized similar works a century earlier (when Lincoln's anti-slavery views were de-emphasized).[268] Journalist and documentary writer Ken Chowder considers Brown "stubborn ... egoistical, self-righteous, and sometimes deceitful; yet ... at certain times, a great man" and argues that Brown has been adopted by both the left and right, and his actions "spun" to fit the world view of the spinner at various times in American history.[15] The shift to an appreciative perspective moves many white historians toward the view long held by black scholars such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Benjamin Quarles, and Lerone Bennett, Jr.[269]

Influences

The connection between John Brown's life and many of the slave uprisings in the Caribbean was clear from the outset. Brown was born during the period of the Haitian Revolution, which saw Haitian slaves revolting against the French. The role the revolution played in helping formulate Brown's abolitionist views directly is not clear; however, the revolution had an obvious effect on the general view toward slavery in the northern United States, and in the Southern states, it was a warning of horror (as they viewed it) possibly to come. As W. E. B. Du Bois notes, the involvement of slaves in the American Revolutions, and the "upheaval in Hayti, and the new enthusiasm for human rights, led to a wave of emancipation which started in Vermont during the Revolution and swept through New England and Pennsylvania, ending finally in New York and New Jersey".[270]

The 1839 slave insurrection aboard the Spanish ship La Amistad, off the coast of Cuba, provides a poignant example of John Brown's support and appeal toward Caribbean slave revolts. On La Amistad, Joseph Cinqué and approximately 50 other slaves captured the ship, slated to transport them from Havana to Puerto Príncipe, Cuba, in July 1839, and attempted to return to Africa. However, through trickery, the ship ended up in the United States, where Cinque and his men stood trial. Ultimately, the courts acquitted the men because at the time, the international slave trade was illegal in the United States.[271] According to Brown's daughter, "Turner and Cinque stood first in esteem" among Brown's black heroes. Furthermore, she noted Brown's "admiration of Cinques' character and management in carrying his points with so little bloodshed!"[272] In 1850, Brown would refer affectionately to the revolt, in saying "Nothing so charms the American people as personal bravery. Witness the case of Cinques, of everlasting memory, on board the Amistad."[273]

The specific knowledge John Brown gained from the tactics employed in the Haitian Revolution, and other Caribbean revolts, was of paramount importance when Brown turned his sights to the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. As Brown's cohort Richard Realf explained to a committee of the 36th Congress, "he had posted himself in relation to the wars of Toussaint L'Ouverture;[274] he had become thoroughly acquainted with the wars in Hayti and the islands round about."[275] By studying the slave revolts of the Caribbean region, Brown learned a great deal about how to properly conduct guerilla warfare. A key element to the prolonged success of this warfare was the establishment of maroon communities, which are essentially colonies of runaway slaves. As a contemporary article notes, Brown would use these establishments to "retreat from and evade attacks he could not overcome. He would maintain and prolong a guerilla war, of which ... Haiti afforded" an example.[276]

The idea of creating maroon communities was the impetus for the creation of John Brown's "Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States", which helped to detail how such communities would be governed. However, the idea of maroon colonies of slaves is not an idea exclusive to the Caribbean region. In fact, maroon communities riddled the southern United States between the mid-1600s and 1864, especially in the Great Dismal Swamp region of Virginia and North Carolina. Similar to the Haitian Revolution, the Seminole Wars, fought in modern-day Florida, saw the involvement of maroon communities, which although outnumbered by native allies were more effective fighters.[276]

Although the maroon colonies of North America undoubtedly had an effect on John Brown's plan, their impact paled in comparison to that of the maroon communities in places like Haiti, Jamaica, and Surinam. Accounts by Brown's friends and cohorts prove this idea. Richard Realf, a cohort of Brown in Kansas, noted that Brown not only studied the slave revolts in the Caribbean, but focused more specifically on the maroons of Jamaica and those involved in Haiti's liberation.[277] Brown's friend Richard Hinton similarly noted that Brown knew "by heart" the occurrences in Jamaica and Haiti.[278] Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a cohort of Brown's and a member of the Secret Six, stated that Brown's plan involved getting "together bands and families of fugitive slaves" and "establish them permanently in those [mountain] fastnesses, like the Maroons of Jamaica and Surinam".[279]

Legacy

Of all the major figures associated with the American Civil War, Brown is one of the most studied and pondered.[280][281] "As a nation, we are unable to get over John Brown."[282]: 89 Kate Field raised money to give to the State of New York for what was to be, in her words, "John Brown's Grave and Farm" (now John Brown Farm State Historic Site).[283] At the centenary of the raid in 1959, a "sanitized" play about him was produced at Harper's Ferry.[284]

In 2007 Brown was inducted into the National Abolition Hall of Fame, in Peterboro, New York.

John Brown Day

- May 1: In 1999, John Brown Day was celebrated on May 1.[285]

- May 7: In 2016, John Brown Lives! Friends of Freedom celebrated May 7 as John Brown Day.[286] In 2018, it was May 5. Spirit of John Brown Freedom Awards were given to environmentalist Jen Kretser, poet Martín Espada, and to Soffiyah Elijah, attorney and executive director of the Alliance of Families for Justice, which advocates for prison reform.[287] In 2022, the day chosen was May 14.[288]

- May 9: The John Brown Farm, Tannery & Museum, in Guys Mills, Pennsylvania, holds community celebrations on John Brown's birthday, May 9.[289]

- August 17: In 1906, the Niagara Movement, predecessor of the NAACP, celebrated John Brown Day on August 17.

- October 16: In 2017, the Vermont Legislature designated October 16, the date of the raid, as John Brown Day.[290][291]

Meetings in honor of John Brown

In 1946, the John Brown Memorial Association held its 24th annual pilgrimage to the grave in North Elba, where there were memorial services.[292]

At the 150th anniversary of the raid In 2009, a two-day symposium, "John Brown Comes Home", was held, on the influence of Brown's raid, using facilities in adjacent Lake Placid. Speakers included Bernadine Dohrn and a great-great-great-granddaughter of Brown.[293][294]

Museums

- John Brown Museum, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, Harpers Ferry, West Virginia[295]

- John Brown Farm State Historic Site, North Elba, New York

- John Brown Farm, Tannery, and Museum, Guys Mills, Pennsylvania[296]

- John Brown House (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania)

- John Brown Museum, Osawatomie, Kansas

- John Brown Raid Headquarters (Kennedy Farm), Samples Manor, Maryland

All of these museums except the one in Harpers Ferry are places Brown lived or stayed.

- Barnum's American Museum in New York, destroyed by fire in 1868, contained according to a November 7, 1859, advertisement "a full-length Wax Figure of OSAWATOMIE BROWN, taken from life, and a KNIFE found on the body of his son, at Harper's Ferry".[297] An agent of Barnum traveled to Harpers Ferry in November, saw Brown, and offered him $100 (equivalent to $3,391 in 2023) for "his clothes and pike, and his certificate of their genuineness."[298] By December 7 the exhibits included "his autograph Commission to a Lieutenancy as well as TWO PIKES or spears taken at Harper's Ferry".[299] On December 16 the Museum added, with document vouching for its authenticity, "the link of the shackles that Cook and Coppock cut in two...that consequently permitted them to escape."[300] Also exhibited were the Augustus Washington 1847 daguerrotype of Brown (see above) and the now-lost painting by Louis Ransom of the famous, apocryphal incident of Brown kissing a black baby on his way to the gallows, reproduced in an Currier & Ives print (see Paintings). The latter was only exhibited for two months in 1863; Barnum withdrew it to save the building from destruction during the anti-Negro riot that broke out shortly.[207]

Statues

- Nothing came of the proposal that Kansas send a statue of Brown as one of its two representatives honored in the U.S. Capitol.

- The first statue of Brown, and the only one not at one of his residences, is that located on the (new) John Brown Memorial Plaza, on the former campus of the closed black Western University, site of a freedmen's school founded in 1865, the first black school west of the Mississippi River. The statue is the one surviving structure of the entire Quindaro Townsite, a ghost town today part of Kansas City, Kansas (27th Street and Sewell Avenue), a major Underground Railroad station, a key port on the Missouri River for fugitive slaves and contrabands escaping from the slave state of Missouri. The pillar and the life-sized statue of Brown were erected by descendants of slaves in 1911, at a cost of $2,000 (equivalent to $65,400 in 2023).[301] Lettering reads: "Erected to the Memory of John Brown by a Grateful People". There is a bronze plaque. In March 2018, the statue was defaced with swastikas and "Hail Satan".[302]

- At the John Brown Farm State Historic Site, near Lake Placid, New York, there is a 1935 statue of Brown escorting a black child to freedom. The artist was Joseph Pollia. The cost of the statue and pedestal "was contributed in small sums by Negroes of the United States".[303]

- A statue (1933) is at the John Brown Museum, Brown's home in Osawatomie, Kansas. It was sponsored by the Women's Relief Corps, Department of Kansas.[304]

- The only other sculptures of Brown are two busts: the first by black sculptor Edmonia Lewis,[305] which she presented to Henry Highland Garnet; and the other, at Tufts University, by Edward Brackett.[306]

Streets

- Only one major street in the world honors Brown, the Avenue John Brown in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, near an avenue honoring abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner.

- A rural John Brown Road is near Torrington, Connecticut, his birthplace. Small roads near museums in North Elba, New York, and Guys Mills, Pennsylvania, are named for Brown. There is a Harpers Ferry Street in Davie, Florida, and in Ellwood City and Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, in Northwest Pennsylvania near the Ohio border, near the route Owen Brown took seeking refuge after the raid in his brother John Jr.'s house in Ashtabula County, Ohio, there is a Harpers Ferry Road, and intersecting with it, a smaller John Brown Road. In Osawatomie, Kansas is John Brown Highway.

Storer College

- Storer College began as the first graded school for blacks in West Virginia. Its location in Harpers Ferry was because of the importance of Brown and his raid. The Arsenal engine house, renamed John Brown's Fort, was moved to the Storer campus in 1909.[307] It was used as the college museum.

- A plaque honoring Brown was attached to the Fort in 1918, while it was on the Storer campus.

- In 1931, after years of controversy, a tablet was erected in Harpers Ferry by the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, honoring the key "Lost Cause" belief that their slaves were happy and neither wanted freedom nor supported John Brown. (See Heyward Shepherd monument.) The president of Storer participated in the dedication. In response, W. E. B. DuBois, co-founder of the NAACP, wrote text for a new plaque in 1932. The Storer College administration would not allow it to be put it up, nor did the National Park Service after becoming owner of the Fort. In 2006, it was placed at the site on the former Storer campus where the Fort had been located.

Other John Brown sites

- John Brown's Fort, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

- The John Brown House, where he lived from 1844 to 1854, and John Brown Memorial,[308] the latter of which is located in the Perkins Park area of the Akron Zoo. The memorial was not erected within the zoo; the zoo incorporated the land where it is. It is not well marked and is not normally open to the public.[309][310][311] When the monument was erected in 1910, 8,000 people attended[308] and Jason Brown, at the time John Brown's oldest living child, spoke.[312]

- The wagon that carried Brown from jail to his execution is preserved by the Jefferson County, West Virginia, Museum in Charles Town.[313]

- A wagon used by Brown when transporting freed slaves from Missouri across Iowa is preserved at the Iowa Historical Society[314]

- An approximate replica of the firehouse was built in 2012 at the Discovery Park of America museum park in Union City, Tennessee. There is a marker explaining the link with John Brown's raid.[315][316][317]

- Iowa has set up the John Brown Freedom Trail, marking his journey across Iowa leaving Kansas, en route to Chatham, Ontario.[318]

- Lewis, Iowa: "Fighting Slavery – Aiding Runaways. John Brown Freedom Trail – December 20, 1858 – March 12, 1859."

- Jordan House, West Des Moines, Iowa.

- "Because of the impossibility of colored boys entering work shops where useful trades are taught", a John Brown Industrial College was planned at Bonner Springs, Kansas, a suburb of Kansas City, and 80 acres (32 ha) purchased.[319][320][321]

Media

Two notable screen portrayals of Brown were given by actor Raymond Massey. The 1940 film Santa Fe Trail, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, depicted Brown completely unsympathetically as a villainous madman and Massey plays him with a constant, wild-eyed stare. The film gave the impression that he did not oppose slavery, even to the point of having a black "mammy" character say, after an especially fierce battle, "Mr. Brown done promised us freedom, but ... if this is freedom, I don't want no part of it". Massey portrayed Brown again in the little-known, low-budget Seven Angry Men, in which he was not only the main character, but depicted in a much more restrained, sympathetic way.[322] Massey, along with Tyrone Power and Judith Anderson, starred in the acclaimed 1953 dramatic reading of Stephen Vincent Benét's epic Pulitzer Prize-winning poem John Brown's Body (1928).[323]